How to price subscriptions

Pricing subscriptions with the share of wallet.

Subscriptions are regarded as the new gold in the business landscape. A promised land where demand and supply happily – or perfectly – coexist with each other.

A land where a flawless balance between creating value and delivering value exist.

A land where the only reason waste exists, is because a data engineer or executive is not looking correctly at data. Or a product manager mistook a decimal for a whole number.

In many ways a subscription to a company has parallels to a marriage. A customer and a company embark on a journey together.

Like in many marriages, a premarital agreement is made. The dominant party takes the lead and dictates the agreement or contract. The customer – a bit shy at first yet blinded by the undeniable good-looking proposal – changes their name to subscriber, much like we call our better half spouse.

The subscriber or spouse must contribute to the agreement somehow. Otherwise they cannot enjoy what the company is offering. Sometimes they do so with time, like with social networks or video platforms. In other cases, it is done by paying a periodical fee for the products or services.

Whatever the case, the business is polyamorous by virtue. The agreement is often tantalizing yet fair. It speaks to many and many wait impatiently to become subscribers, members, users or spouses.

Yes, when the company goes to other markets it sometimes changes its agreement to match the local demand or authorities, but it generally tries to keep all spouses happy. In many cases, the community even bands together to share their joy for being part of the vast network the company created.

The company finds that cute and adores it. It loves to call that branding and sometimes likes to package it delicately and put a nice sticker on it. The sticker often resembles the shape of a capital S with an intersecting vertical line or an E with two dashes in the middle instead of one.

The spouse, at first, is just blinded by, what one can surely call, love at first sight. Everything seems so rosy and bubbly. So perfect.

The spouse is so happy to finally find a company who truly understand their needs and desires. So happy that they found something that made their lives better, even if it is just a tiny inch.

Not only that, but they always remember birthdays, celebrates milestones, names them by their first name and never misses what is supposed to deliver. Not even once.

As time goes by the company seems to be more interested in the subscriber. They know what time they wake-up, what type of things they are interested in, where they have been or are going to, what type of device they prefer, they even know what pains them and what keywords they have typed in the past.

The company is so in sync with the subscriber. It even feels like they think alike. The company often finish the sentence of the subscriber, they know what to do when the subscriber is sad and knows how to celebrate when they are happy. It feels like the company has known the subscriber for eternity.

The company is very thoughtful. It sometimes offers something extra in exchange for extra time or wealth. The subscriber may have never asked for it, but it does seem like they know the subscriber better than they do themselves or their actual spouses.

As time goes on the subscriber gets exposed to other similar companies whom offer similar services or products but not exactly the same. Sometimes subscribers get seduced to switch companies, like with utility companies. In other cases, they get lured by having a polyamorous relationship themselves. In very rare occasions, a subscriber may want to end all these relationships and become, well, celibate.

However, the companies will never forget that one has become celibate. Always trying to lure a celibate is easier than someone whom has never participated before.

In any case, the subscriber gets more often exposed to these types of relationships. Sometimes they wonder how these other companies know who they are and what drives them. Other times they question why would they spend time talking to them, can they not see that the subscriber is already unavailable?

Yes, the subscriber may be unavailable, yet these other companies know better. They know to who they are talking to, what they like, but they also know what is inside their wallets. They know what their share of wallet is. They know what a tantalizing price point is.

Subscriptions

A subscription is no more than a contractual agreement between a company and a customer. The contractual agreement can be defined as a promise for a company to deliver a recurring product or service to a customer whom pays a periodically fee for that product or service.

If you followed the narrative before, you likely spotted some of the benefits and downsides of subscriptions.

To not reiterate and summarize the previous piece. The customer does generally receive convenience at a price point that is generally deemed either more economical or acceptable than alternatives – though, there are cases were both are not true.

The customer does pay for the convenience, whether they want or use the product or service or not, and the customer does pay with data.

On the other hand, the company gets a steady stream of income and has a fixed customer base. The business builds around the relationships it has with customers.

It does that in many shapes, forms and sizes but it generally boils down to becoming more efficient and creating an increasingly better value proposition for customers – and to keep the competition at bay.

The meta of subscriptions are multiple and we are not going to delve into it. However, it is important to stop and understand what subscription does to customer acquisition, retention and loyalty.

Although they are not necessarily important to know how to price a subscription, they are important to understand the mechanisms of subscriptions.

Subscription: Customer acquisition, retention and brand loyalty

Customer acquisition is generally regarded as an expensive endeavor with subscriptions.

From the customer perspective you are locking them in a contractual commitment for a period of time, for something they are not sure if they will use for that specified period. Essentially a company is asking a recurring fee for something they are not sure they will need for a sustained period.

Some companies get around that by playing to the belief systems that are already in place. For example, insurances (what if?), utility companies (I want to be warm or I want to cool off) or telecommunications (I want to be accessible) or even gyms (I want to be healthy). Other companies must invest into changing habits, whether it is with marketing or a proposition that is much better than current alternatives.

Whatever the case, habits can change and once changed, they tend to stay for a longer period of time. To exemplify, a miner during the industrial revolution would have likely been gobsmacked at the idea of paying for health or life insurance, despite the risks involved in mining during that period.

With retention, particularly millennials (or generation Y) are considered, broadly, as a demographic group that are not brand loyal. This is a trend that is recurring in other demographic groups as well. Brand loyalty is becoming more complicated as clients view relationships with businesses as a functional transaction rather than a preferential (recurrent) transaction (i.e. the customer wants whatever it wants, whenever it wants and does not care where it gets it from as long as it fits the price they are willing to pay).

This means that brand loyalty does not necessarily affect customer-lifetime-value. For example, if you buy coffee or tea from a Coffee Company, a Starbucks, Blue Bottle or any indie coffee shop and you really like the coffee of any one of them, would you go out of your way to buy a coffee there? The chances are that you have bought coffee elsewhere. A study on it, has shown that half of Starbucks customers have purchased coffee from competitors.

Functionality in the transaction is the results that customers have a pre-conception of what they expect. Meaning that meeting customer satisfaction is self-evident for customers, as many will meet an average standard, thus making brand loyalty on functionality difficult to obtain. In other words, if you walk-in a coffee shop you would expect there to be helped with a smile, that they have your favorite cup of Joe, that the price is in between two and five euro’s, that they misspell your name on the takeaway cup and that they serve you on time.

Subscriptions and retention can go hand in hand. Some companies lock customers in with contracts, like a yearly contract with automatic renewal. Others make it difficult for a customer to unsubscribe, with whatever barriers companies come up with.

Retention and brand loyalty are something different though. Brand loyalty must be earned while retention can be contractually demanded with subscriptions. Nonetheless, the ideal situation would – always – be that a customer remains a subscriber because they are satisfied customers.

Now, when a company has acquired, retained and made significant effort to make a customer loyal, that still does not mean that a company has all the business opportunities covered.

Like previously stated, customers can and do make use of alternatives. We will delve into it by looking inside the customers wallet.

If you would like to know more about how a subscription company works, I encourage you to check a previous article I have written about subscriptions in the food industry.

Share of Wallet

or Share of Customer

Share of wallet (SOW) is a concept that was created by the financial sector to understand how individuals spend money. The function is to answer the question: how much money does a customer spend on candy bars (category) and how much of that does it spend on a brand?

Essentially the wallet or disposable income of a customer gets divided into categories.

Between all categories a customer spends a certain amount of disposable income.

The income spent in any category is distributed between several companies. Depending on how much is spent on one or several companies, the company enjoys a higher percentage of the customer expenditure.

Hence, it has a larger share of wallet from that customer.

Imagine a customer has one hundred euros to spend on candy bars a month. The customer buys 50€ worth of Mars, 30€ worth of Milka and 20€ on Kinder Bueno. The Mars bars would have 50% of the share of wallet, Milka 30% and Kinder Bueno 20% from that hypothetical customer.

Share of wallet has some similarities with market share and disposable income expenditure (or consumption). Market share function, however, is to calculate the percentage of revenue a company has in the total market. Disposable income expenditure on the other hand, shows what people spend on categories not what they spend on specific companies.

There are a few ways to figuring out what a customer spends on category. The easiest would be to ask customers directly (survey) and/or use the governmental databases about domestic consumption.

Other options would be to hire agencies or bank whom sell that information – yes, they really sell that data.

Wallet Allocation Rule

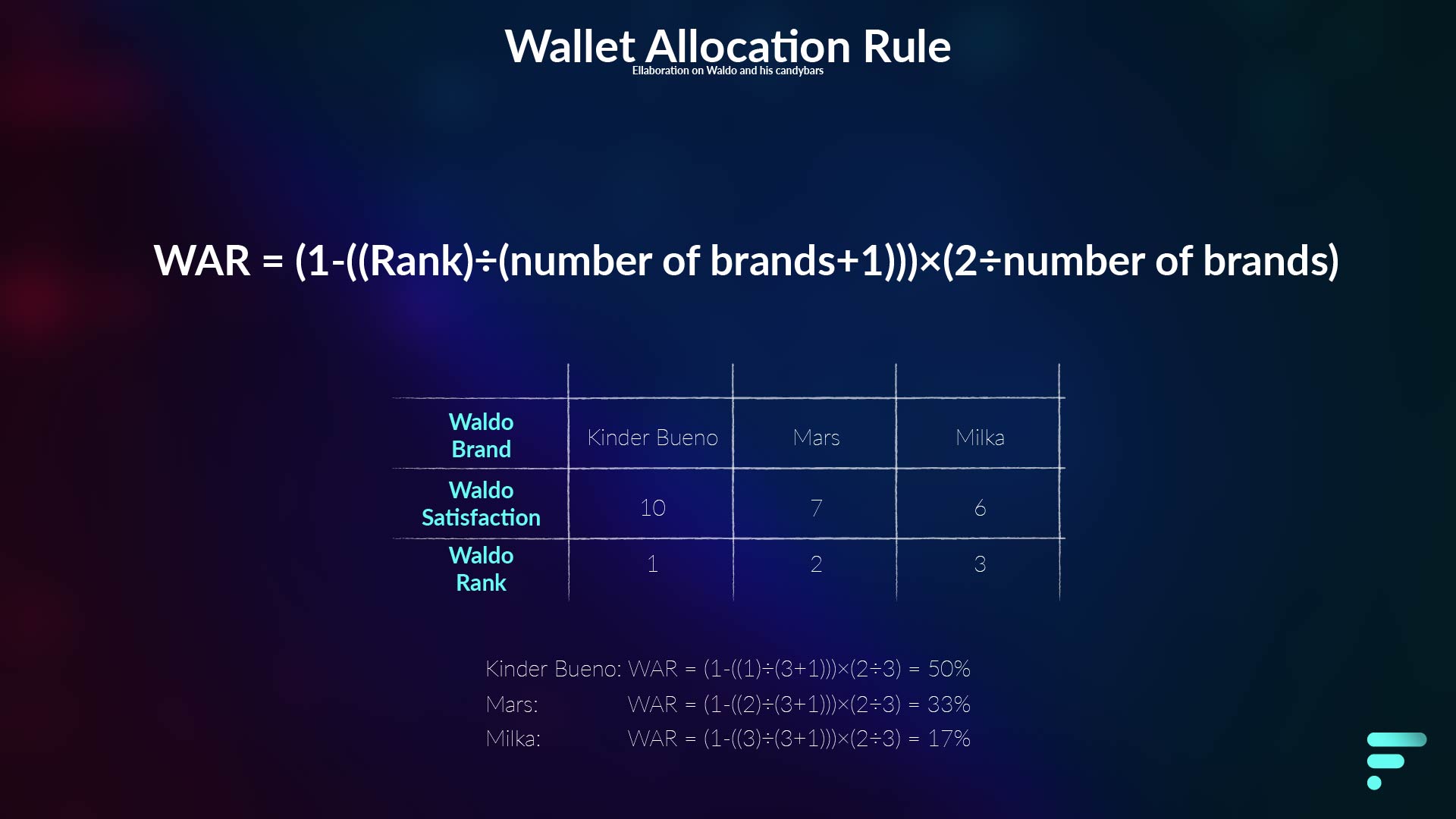

Other methods used by consultants are the Wallet Allocation Rule (WAR). The equation was developed by a few authors, to accurately predict the share of wallet of customers with data that you may already have.

WAR = (1-((Rank)÷(number of brands+1))×(2÷number of brands)

The idea behind it is to by-pass the loyalty metrics to something more tangible and consequential for business: sales.

The equation of the WAR departs from the point that customers do buy products and services from competitors. By figuring out how many of those companies they use and how they rank them in customer satisfaction, you have enough ingredients for a very close approximation of the share of wallet.

For example, Waldo buys three different type of candy bars. Mars, Milka and Kinder Bueno. Waldo ranks in satisfaction Mars as a 7, Milka as a 6 and Kinder Bueno as a 10. Kinder Bueno would rank for Waldo as 1st, Mars as 2nd and Milka as 3rd.

The Wallet Allocation Rule equation and an elaboration of the equation can be seen below.

With the information above, one can conclude that Kinder Bueno has 50% of the share of Wallet from Waldo. Mars would have 33% and Milka 17%.

Needless to say, this method is not perfect, and in some cases even counterproductive.

When information is not available about competitors and the preference customer has for competing products or services, one may question if it is not better to ask customers directly about how much they spend on category and merge that information with sales information a company has available.

Alternatively, one can ask what customers think they spend on a brand, when merging information is too challenging for a company.

Instead, with the WAR the preference goes to knowing what brands customer use – which is indeed very useful for competitor analysis – and to rank them to come to, arguably, the same information. In essence, a researcher is asking different information than what they would like to know, which is knowing the share of wallet.

Moreover, the result of the WAR is not waterproof either. The equation is an approximation, and the model behind it assumes that the highest-ranking brand has the lion’s share of the wallet.

Subscribing to the Share of Wallet

Knowing what the share of wallet entails, the next part is to figure out how subscriptions fit in the wallet of customers.

Subscription are kind of a different breed in the sense that they secure a certain portion of the wallet for a sustained period.

The ideal situation for a subscription-based service or product is to attain all that is in the category the company is active. The outcome is that retaining customers will require significant less effort, provided that the company meets the level of satisfaction that is expected. Much like utility and telecommunication companies do – yes, the majority seems to be dissatisfied with them.

So how do you achieve that? By knowing exactly what customers current expenses are in that category. Some companies, whom do not work with subscription, have done that before. Think of coffee companies serving food in addition to coffee, or fast-food restaurants serving breakfast in addition to lunch and dinner.

Subscription companies can go a similar way. A meal-kit delivery company may only deliver dinners, but can also deliver breakfast, lunch and a midnight snack encapsulating the category of food. Telecommunication companies do more than just let you call over a distance, they offer internet access and even help with financing phones. The proposition of mobile phone carriers can sometimes be good enough for customers to drop internet access at home, entering with that, arguably, a new category.

Pricing subscriptions with share of wallet

One can flip the theory behind the share of wallet to come to a pricing strategy.

There are many different pricing methods and strategies around, but it is my opinion that share of wallet deserves some attention in the process, particularly since subscriptions try to secure part of the wallet.

Of course, there will never be a pricing structure that fits every individual and not all customers are made equal, but knowing what the share of wallet is can give a company a better indication of how customers perceive the value that they are getting when agreeing to a subscription.

There are four things you need to know before proceeding: who are your customers, how much they spend in the category you are active, from which competing companies they buy products or services and how satisfied they are with the competing companies.

Some information you will already know. Other times conducting a survey will give concrete answers. When your organization is still small or in the preparation phase, you can also talk to potential customers.

Who are your customers or target group?

Customers, or at the very least the target group, should be the individuals who are committed to subscribing to what a company is offering.

This information is essential from any point of view. During the segmentation phase, keep special attention to the disposable income.

You will need that information to come to a better understanding about how to price and position a subscription at a later stage.

Perhaps unnecessary to mention, but not all companies can function on a subscription base, you will save a lot of headaches by figuring out if subscriptions are even viable for the business category you are in.

In the case you are just starting or considering switching to a subscription model, you need to know what part of the segments the company will primordially focus on.

Once you have narrowed down who the target customer is, you need to figure out, like previously mentioned, what the disposable income is.

How much do the customers or target group spend in the category?

Information about category expenditure can be obtained in a few ways. The quickest is to search the databases of governmental statistics bureau.

Some countries have data by region and even some cities have their own databases, where data of citizens are freely available.

Pay close attention to the categories. In some occasion’s categories are split to specific product groups which will give a much better indication of spending patterns. If percentages are available, take that information.

More importantly though, make sure that the category of expenditure you are looking for matches the target group. Although this is not always possible, keep in mind that there are notable differences on spending patterns in different segments and social classes. For further reading, look into Engels Curve and Engels Law.

Alternatives to the previous option, or even supplementary, is to conduct a survey. Another possibility is to look for third party information. Some consultancy agencies, industry syndicates, magazines or economists investigate the spending patterns and write papers on it.

Since knowledge about the target group has been gathered in the previous step, you can extrapolate how much the target group spends on a category and come to some estimations.

On which companies do the customers or target group spend the allocated budget on a category?

Competitor information is best obtained through a survey. This will provide with accurate information on companies the target group are using.

Asking how much the target group spends on competing companies can be tricky for some products or services. You can resort using rating scales to tackle that problem.

Alternatively, there are other methods of obtaining a proxy on that information. However, they are not favorable for different reasons.

Sales data or market share data can provide you with a lot of information on competitors. One can draw conclusion on pricing, positioning and many other aspects. This method can be viable for product groups that are broadly available, like for example with frizzy drinks, or public companies that sometimes disclose information.

For segments that are very narrow, where data is not available, one can resort to doing physical research. For example, if an entrepreneur is planning on opening a restaurant specialized on Poké bowls on subscriptions, one can visit competing restaurants, talk to potential customers, count tables and chairs, usage percentage, turnover rate and so-on.

How satisfied are the target group with the offering of competitors?

Rating satisfaction is best done through a survey along with the previous question. You will want to know both points so you can understand which companies are seen as competitors by the target group and how satisfied customers are with using those companies.

Rating satisfaction in a survey can be done in numerous ways. Rating scales or Likert scales are best suited for this. Even a glorified rating scale like the Net Promoter Score can be used.

There are not really alternatives that should be used to get this information.

Some consultants or entrepreneurs may opt to use reviews scores to come to this knowledge, but that information cannot really be used to measure satisfaction level. You can read some of the reasonings here.

Subscription Pricing with the Share of Wallet

Now that the necessary information is collected, we can use that information to make some careful assessments on how to price a subscription.

During the first and second step, we have figured out what the budget of the target group is for a category. Next is to figure out which percentage a company can realistically attain. This can be set as a target or can be measured by what a company is offering in contrast to the budget allocated in the category.

For example, the dollar shave club can attain 100% of the budget of razor blades from its customers. While petrol-stations will never be able to attain 100% (unless they change the business model) but can, with loyalty programs, get, hypothetically, 50% of the share of wallet.

Knowing what percentage a company can attain with a proposition is important for two reasons. One, what percentage of wallet can realistically be secured, thus knowing what price a subscription can be to meet customers current allocated budget. Two, what other opportunities are there to grow and fully attain the category in the wallet.

During the third step, there is a clear indication of what alternatives are used by customers. Although this information is on itself very important for competitor’s analysis, the information becomes stronger by knowing what customers spend on these companies and, even stronger, by knowing how satisfied they are with the alternatives (fourth step).

Knowing who competitors are and what they charge for their products or services is already on its own a method to come to a pricing strategy. However, by knowing how much customers spend on it you can also have a good clue on how much volume is bought. More importantly though, you can calculate what percentage a company has of the wallet.

How satisfied customers are with a competitor will help you to assess on which grounds you can compete. Very satisfied customers will be hard to persuade to change brands, while unsatisfied customers can fuel growth. Moreover, knowing satisfaction levels can help a company whether offering extra or fewer features can win customers over, provided it is priced correctly.

Lastly, by knowing the used brands and the satisfaction levels on each of those brands, one can use the Wallet Allocation Rule to come to an estimation to which company has the lion’s share of the wallet.

With the information above, an entrepreneur or manager can come to a good estimation on how to price a subscription to the means a customer has.

There are many catches to this way of pricing. Share of wallet can fluctuate greatly per household per month. For example, some months someone will spend more money on coffee than others. In other months someone will spend more on holidays than others.

Moreover, share of wallet does not take into consideration what a product or service is worth for a customer. Pricing a subscription on share of wallet instead of perceived value, constrains the company by missing opportunities. For example, if a service called Netflix Premium existed, where a very large movie catalogus would appear at five times the normal rate, would you consider switching? Personally, I would not, but if the licensing problems in motion pictures and streaming services where the same in music streaming, I would consider switching.

Share this Page