360 Deal

Artists, influencers and business model.

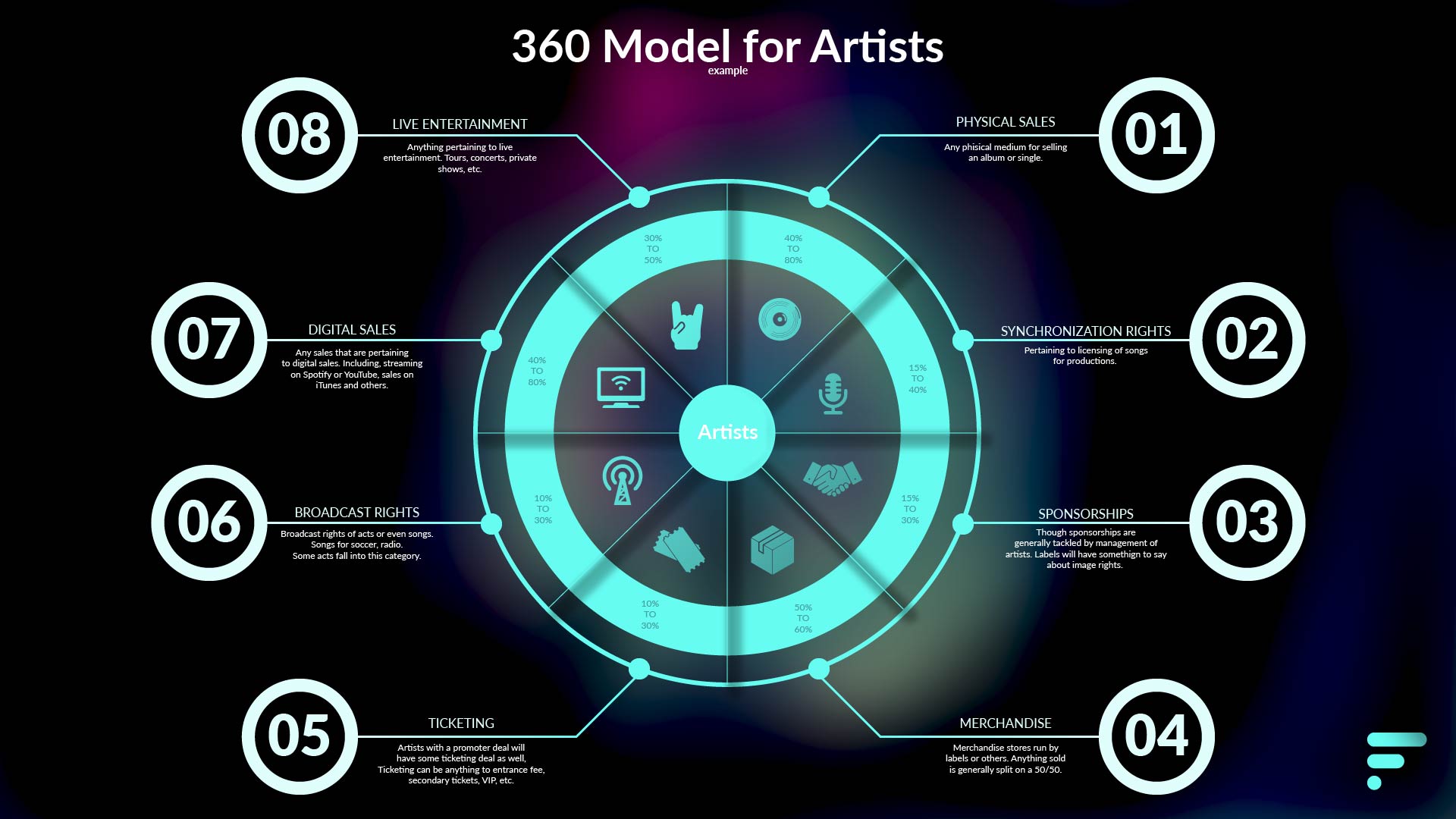

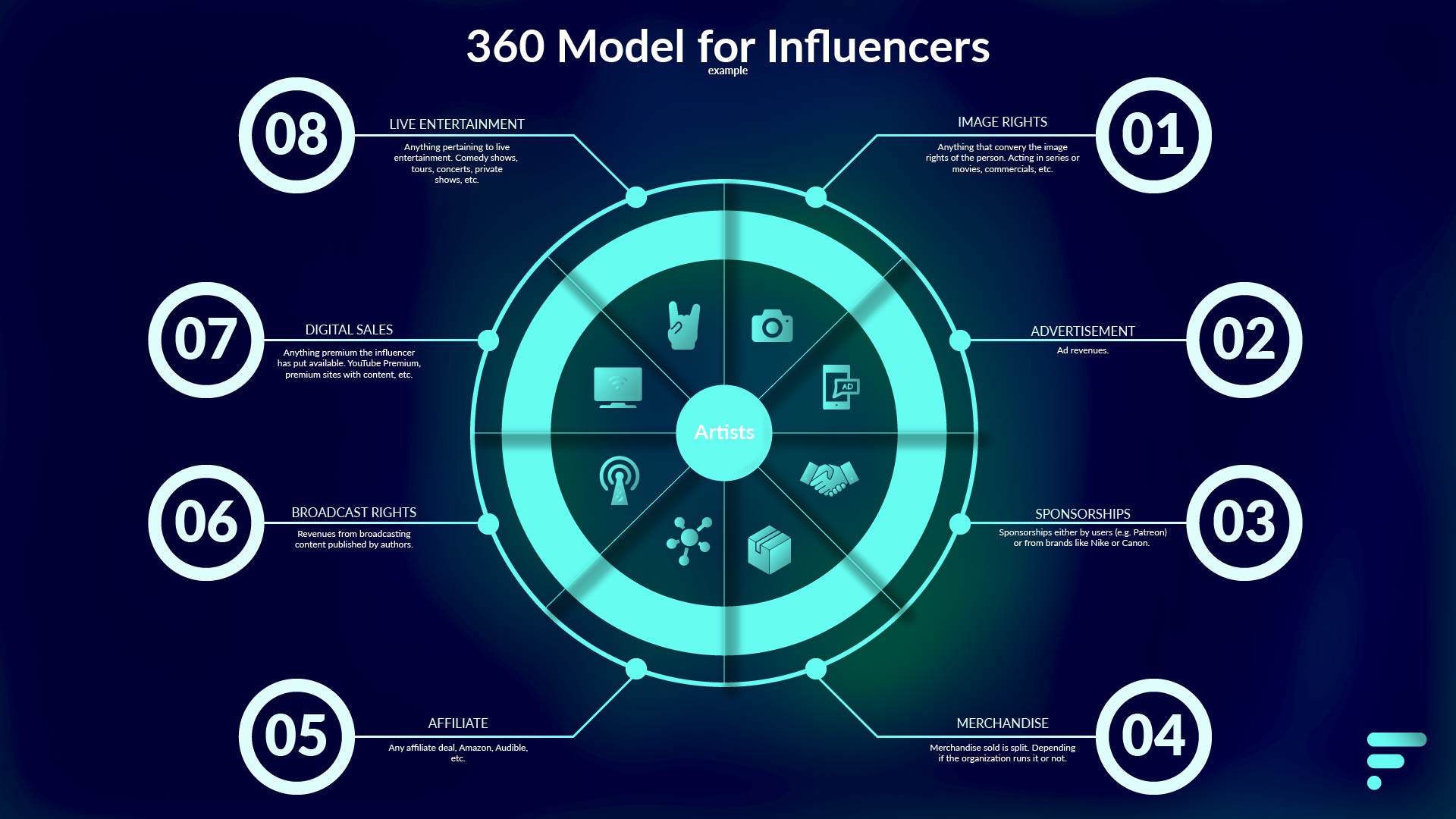

A360 deal or multi right deal, is commonly used in the music industry to outline the legal relationship of an artists with a record label. The consensus is that the relationship between an artist and a record label intensifies due to that the later shares all revenue streams of the former. The artists, on return, can expect help with production (both in capital and knowledge), promotion and monetization of his or her craft.

In other words, with a 360 deal, a record label takes a cut of merchandising, live-performances, sponsorships and any other revenue stream. The artists, on the other hand, can expect to be helped to become larger than what he or she would have been able to achieve on its own. At least in theory.

The popularization of the 360 deal came by the time the recording industry was facing problems with P2P file sharing platforms. During this period users would share records with each other, bypassing in the process the monetization system put in place by the music industry.

The 360 deal, or the model thereof, is interesting because of the many forms it can take. The model is not only used in the music industry, but there are many other industries that use the model to increase revenue of both the company and the exploited subject. Companies that have a luxury position when it comes to exploitation of any unique resources can benefit from this model. Be it talent, positioning or knowledge.

Throughout this article we explore three major points. In the artists section we explore how the model eventually came to be and explore the corporate foundation. During the influencers section a case is made why this group are in line to experience similar 360 deals (bear with me on that) or a variation thereof. Lastly, we will be looking at the actual business model and how to make it work from a business development perspective.

Artists

There is no denying that in the current day and age artists are not able to get a traditional record deal – that is that the artists only share revenue from their actual records – anymore. Any record deal will have some form of revenue sharing across the different income streams an artist can generate.

The base foundation for the 360 deals are multiple, yet most are rooted in the past.

Artists, users and record labels: quick rundown of the record industry

Though record labels have always been identified by public opinion as art extortionists, there was a time record labels would generate enough income by selling records that other revenue streams were not pursued.

The consensus on a normal record deal, was that the record label would take a higher cut on selling records, including owning the songs. While artists and their managers could profit from ancillary sales. This was the status quo until an external factor changed that.

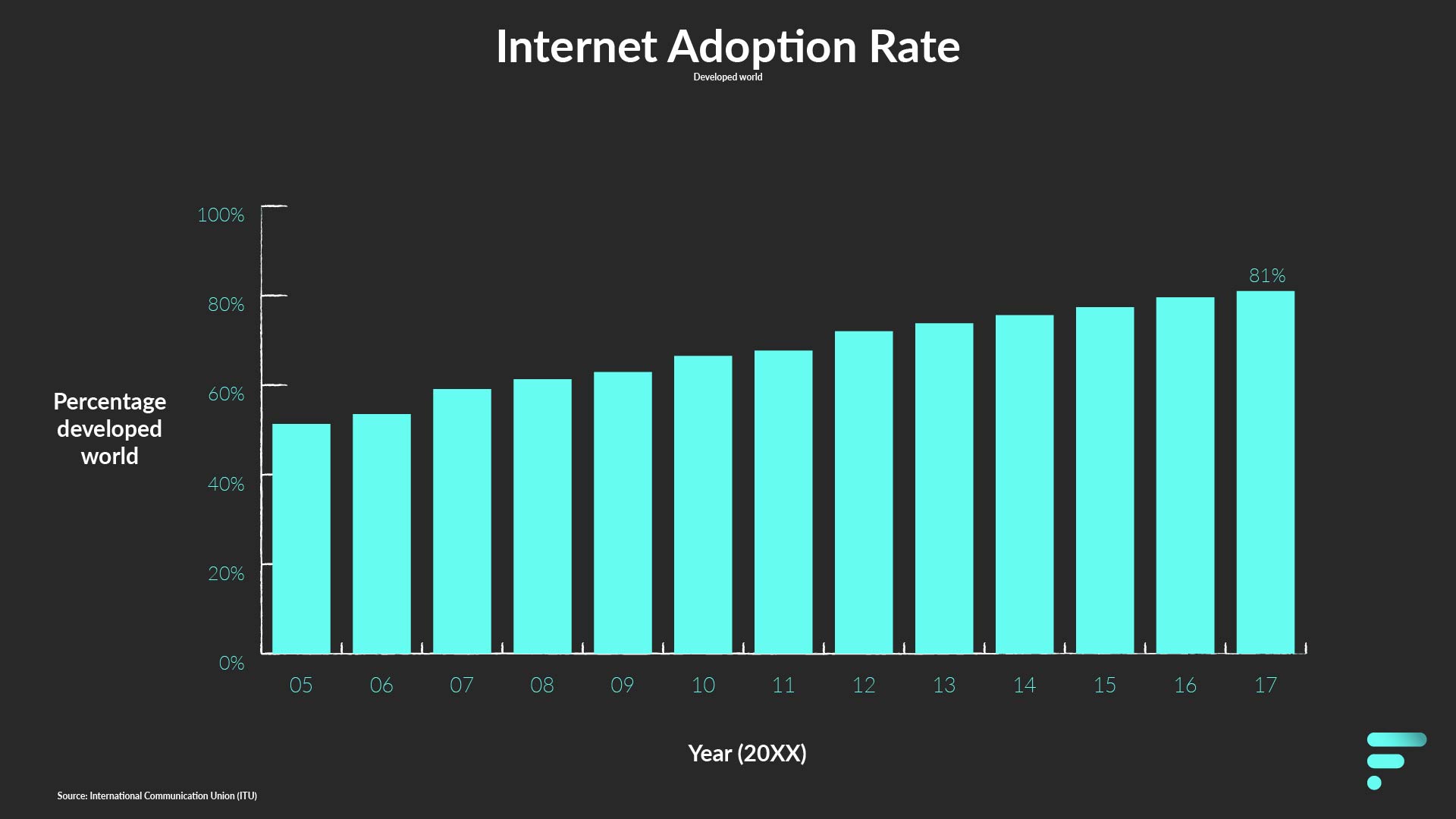

In the late nineties and early noughties, internet access and internet adoption rate exploded. The mainstream usage of internet brought a new dimension in business that was never explored before.

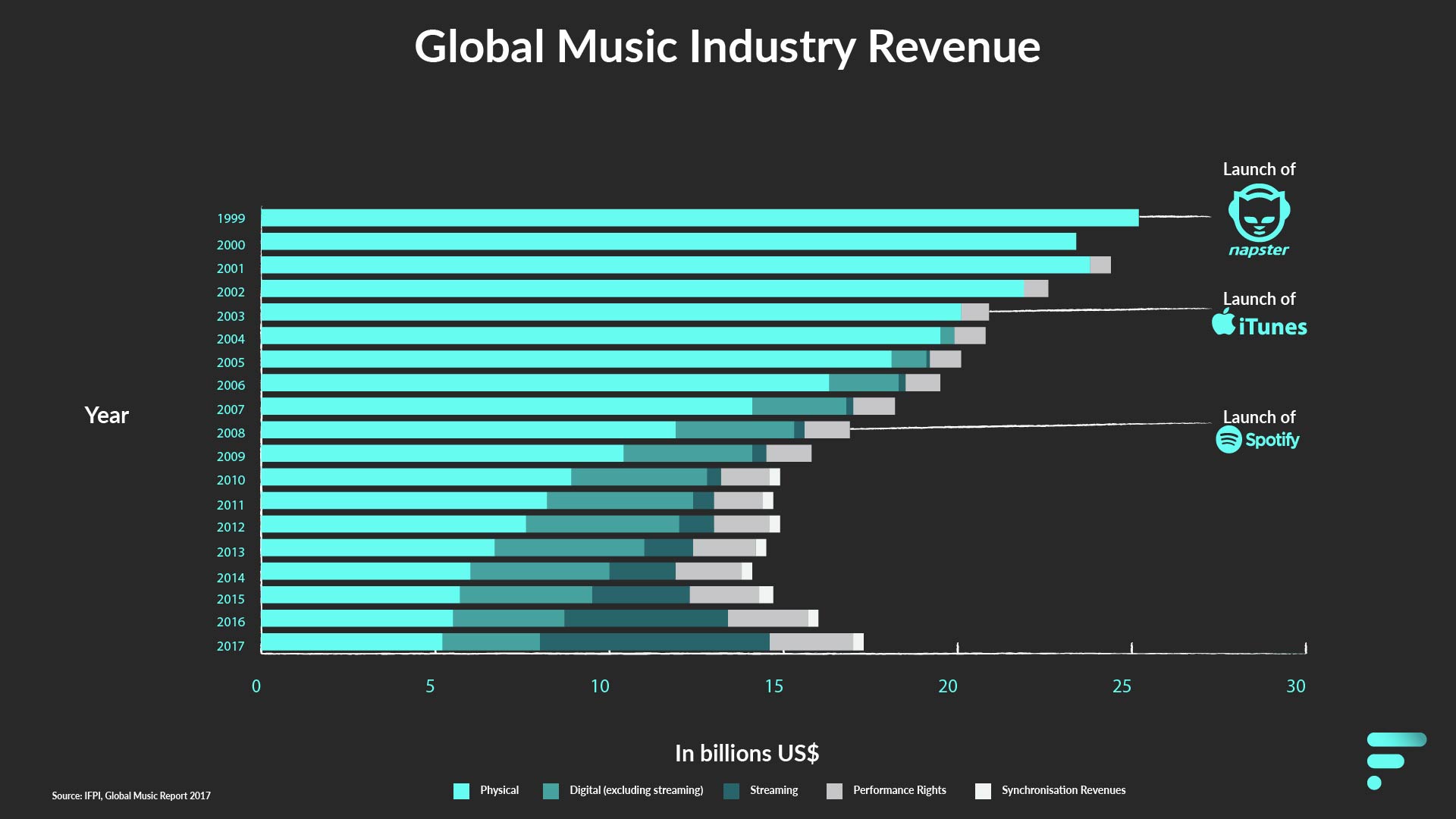

New ventures started to emerge on internet. One of those ventures, Napster, caught on like wildfire. Napster offered something no one else had ever done before – at least at that scale – easy access to free music.

Napster was just the start, it opened the floodgates for similar file sharing ventures like Kazaa and BitTorrent. Though it was the demise for record sales, artist suffered a similar fate with other platforms being launched in the mid and late noughties. Platforms like YouTube, or any other social platform for fan engagement, opened the floodgates for uncurated artists to enter the fray. The excess of new up and coming artists made it difficult for new and old artists to find their positioning, which is displayed in how 360 deals came to be.

Users did not go unscathed either. Record labels decided to take the legal approach for illegal consumption of music. Backing anti-piracy lobbies, suing peer-to-peer providers and suing users. Needless to say, this led to friction between users, labels and artists.

Labels favored protecting the system that was in place and did not make concrete steps to pivot their business model quickly enough. Which resulted, in hindsight, for a loss for the music industry.

The cascading results of poor decision making throughout the digital era by labels is evident when looking at the process labels went through to fix the situation. It first started by legally prosecuting anyone threatening their business. Next, it resulted in labels reducing the price of their products (CD’s) in the hope people would buy CD’s instead of downloading them. Next, labels decided to make music scarcely available online, like on iTunes, instead of creating a platform as they had both the license and publishing rights – and by extension having access to an exclusive monopoly. Lastly, labels offered their music library to streaming sites for a fraction of the profit they once made from records.

Though easy to dismiss in hindsight, one must remember that the different contractual obligations and systems in place put by music corporations made it difficult to adjust quickly enough in the new era. Digital was just moving too quickly for record labels. Think of physical distribution, creation of CDs, album recording instead of singles, etc.

In fairness, there were some music executives that have gone on record, like Jimmy Iovine, to look for alternative monetization models in the recording industry in the mid noughties. In Jimmy’s case, he, allegedly, was looking into streaming options and digital sales after Napster came to his attention. Later, he would stumble on Apple, whom was developing iTunes, and played a part with making iTunes happen, from a licensing perspective.

360 transition

With a new influx of artists and a regression in record sales, labels had to come up with a business model that would make more sense to recoup the profit once made. Labels made the connection of what artists wanted (e.g. promotional support, advance, tour support) and what labels offered (e.g. capital and support), labels had the better negotiation positioning. Moreover, labels sought profit revenues beyond record sales, as the assumption was that the labels and their investment is what made the artists (hot) sought after.

As a side note, on why labels started developing higher profits margins. In the past labels would sign several artists in which the label did not know if they would break-even. This led to several artists becoming a loss for the label (as a side note to the side note – according to IFPI between 1.4M US$ and 750K US$ is spent on new acts to break to the public).

The loss needed to be countered, therefore the model was always designed that one out of twenty acts would be successful to balance the loss or break-even. This meant that if a label was able to break artists two tenths of the time, the label in question would be considered a success in the music industry. Eventually everything in the music industry would become more sophisticated as labels would be better at breaking artists and reducing costs, but the percentages stayed the same. This in turn would become the golden age for record sales, before plummeting during the internet era.

The 360 deals led record labels to extend the services they would offer artists. Eventually labels would pivot into firms that supported artists in a myriad of ways at a cost of sharing the revenue in all those areas. Simultaneously labels would wage war against piracy. From thereon, record labels did not have as a sole focus selling records but conveyed their companies in supporting the artists in all other areas interesting for the labels and artists.

Moreover, this meant that the hegemony of labels started to break, allowing other companies to enter the music industry in different ways.

Though out of the scope, the largest promoter in the world, Live Nation, started looking into 360 deals with acts like Jay-Z and Madonna. Later Apple started exploring exclusivity in music with artist like U2, under the reign of Jimmy Iovine. While YouTube, at the moment of writing this article, under the reign of Lyor Cohen, is exploring different ways of exploiting the music on the YouTube platform and the accompanying videos.

So, whom is the founding father of the 360 deal? There are different accounts to that and there are different forms the deal has taken. Lee Marshal states that EMI conceptualized the model and disclosed it to the public somewhere in 2002, while Live Nation, a promoter, did the same with artists in 2007. Moreover, music executive Lyor Cohen has credited himself as the creator of the model, if not the most vocal executive to praise the model, when he was an executive at Warner Music Group.

Changes in the 360 deal

Although the influx of new artists that started using new promotional channels (read: YouTube, Facebook, SoundCloud, etc.) may seem unimportant in the mid to late noughties, it increasingly became more important in the future.

By the twenty-tens it became one of the main influencers for artists being able to get a record deal. Labels could scout with open-data if there was a product market fit. An artist with no online traction would be quickly dismissed for other talents that have done the necessary for their crafts to be heard.

Moreover, the advances internet brought in the twenty-tens opened other options for artists. Working on their career while not being affiliated with a label other than their own. Allowing artists to stay independent.

Sites like Patreon, GoFundMe and any other crowd funding site, private or angel investors, even brands that want to be associated with an act, promoters and many others. This all has affected the transition of 360 deals to something more malleable and fluid instead of a rigid model

Influencers

There is no denying that artists have always been influencers of culture. Artists have generally sought and enjoyed some form of spotlight. Generating attention with their art and craft. Attention that can influence the buying decision of many.

Companies want to have attention and turn that attention into sales.

Both are derivate of human’s problem with grandiosity.

Influencers have been around for many generations but not always in the most obvious ways. While companies may not exercise direct control over your friend, a friend may be able to persuade you to buy a certain clothing item or gadget. Yet how that friend is persuaded to persuade you (or influencing you), is what we will be exploring a tad further.

Influencers can come in many different shapes and forms. Early examples can be found in the tobacco and alcoholic beverages industry. Companies active in those sectors have hired charismatic people (read: influencers) to manipulate buying decision in, for example, a pub (in business terms personal selling or social selling). Although, it may seem like something a company would do a long time ago, it is still used as of today.

Nowadays, it may seem strange that someone charismatic during a nightlife event may offer you a free drink or some cigarettes – even suspicious – but companies and marketing agencies have not forgotten the impact it can have on branding and sales.

Companies and marketing agencies have understood the influencer effect early on, but not always exploited it to the most of its extent in the past.

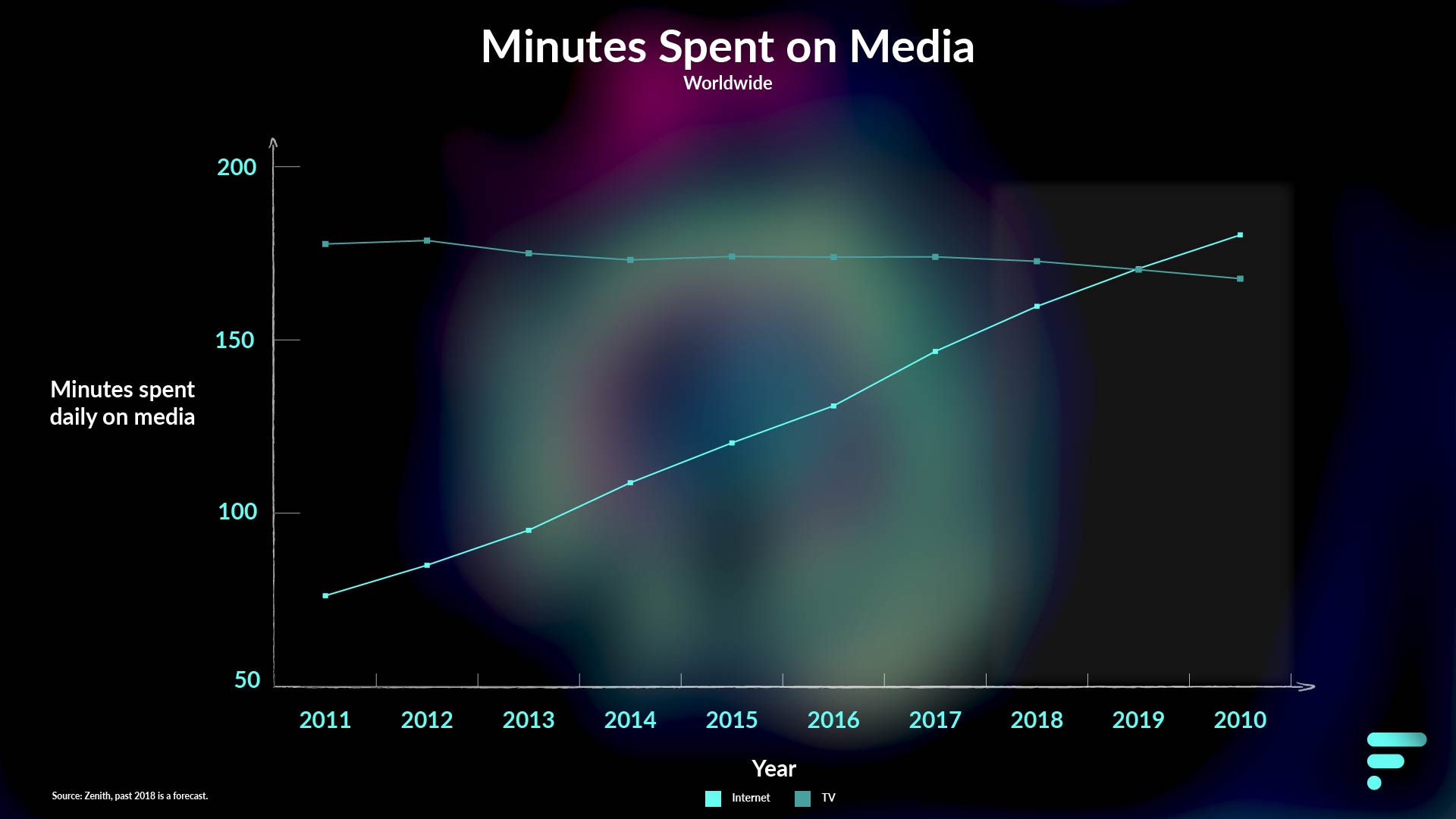

However, in the late noughties and twenty-tens something different started to happen. With the rise of new platforms like YouTube and Instagram, attention of audiences started to shift to digital. From thereon the modern-day influencer was conceived.

The rise of new content creators on these platforms and the attention they have garnered, have disrupted the way entertainment is consumed. Fragmentating the market and paving the way for individuals to become influencers.

Families are not sitting next to each other hunched over television, instead they have their own smartphones and are watching YouTube on their own.

Rise of the influencers

There is no denying that influencers, like artist, are beloved by their community. The similarities between one art form and the other are very striking. They produce art on a regular basis that is enjoyed by many. Although their expertise differs, the results are somewhat the same. Having access to an individual’s attention.

The fragmentation of the media landscape by these new influencers has brought a different way of targeting and measuring an audience. Where previously companies had to navigate the media landscape to pay for gross rating points or GRP – do not worry we will not get into that –, today companies have a wealth of accurate data. Making it more efficient for companies to target an audience that narrowly fit their target group.

In other words, metrics have been developed to know who watched what video, who read what article and who listened to what podcast. Since the amount of influencer –but more importantly viewers–, has steadily increased, it has become an important and effective channel for companies to communicate on.

Moreover, the sheer number of influencers has given opportunities for companies of any size to work with them. Think of small and big cosmetic companies working together with beauty influencers, technology companies with tech influencers or a unicycle company with a unicyclist.

Consolidation of the influencers

Online media consumption has grown exponentially over the course of a decade and it is unlikely it will stop. Indeed, the trends with digital first audiences are positive and have always been positive since the first time YouTube launched.

Like with any fragmented market where there is potential for growth. Eventually, there came a time where a few entrepreneurs try to consolidate the market. Bringing influencers under a larger umbrella is a normal development for many reasons. Think of economies of scale, negotiation position, security, cost reduction and many other options.

Although it may seem that influencers, unlike music artist, are broadly perceived as a category where it is easier to stay independent, it generally does come at the cost of losing opportunities.

So which companies are functioning as a record label for influencers? The simple answer would be any media company or network working towards folding influencers in a network. In the early to mid-twenty-tens, these networks would be called multi-channel-networks (MCN).

How MCNs or similar entities operates is strikingly similar to record labels. Funding, investment, help with production, access to production facilities, promotion, access to sponsors, legal help, marketing or a higher percentage of ad revenue.

In contrast when an influencer works with an MCN they must share revenue from all sources of income and in some extreme cases sharing the intellectual property rights.

Due to the fast growth and the potential influencers in several segments had, MCNs and similar organizations started acquiring many influencers. Big and small. All with different types of deals.

From forward committing incentives for creators – for the now defunct Viners even committing to six figures guarantees – to IP sharing with the company. By acquiring more and more creators these corporations started growing exponentially MCNs priority shifted to monetization: organizing events, selling merchandise or anything else that brought revenue.

The potential of these companies did not pass by unalerted. Due to its potential in targeting digital only audience, MCN’s have been acquired by larger corporations. Maker Studio has been folded under Disney for 675M US$. Warner Media acquired Machinima. Or AwesomenessTV by Viacom. To name just a few examples.

Companies that have ample of experience with exploiting and capturing intellectual properties.

360 deal business model

The 360 deal is a model that uses one pivotal component to generate revenue from all possible streams. Throughout this article we explored individuals (artists or influencers) as being that specific pivotal component. Though true in the nature how the model is generally known for, it is, however, not necessary to have a physical person playing that central role.

A scarce resource should be, in theory, sufficient for that pivotal role. Knowledge, brands, distribution system and any other scarce or unique resource could take upon that role. Although proprietary resources (e.g. patents, intellectual property, etc.) can benefit the most for this type of model.

That proprietary resources are well-suited is twofold. The legal categorization of the proprietary resource and the distribution of that proprietary resource (licensing, franchising, alliance, etc.).

360 model

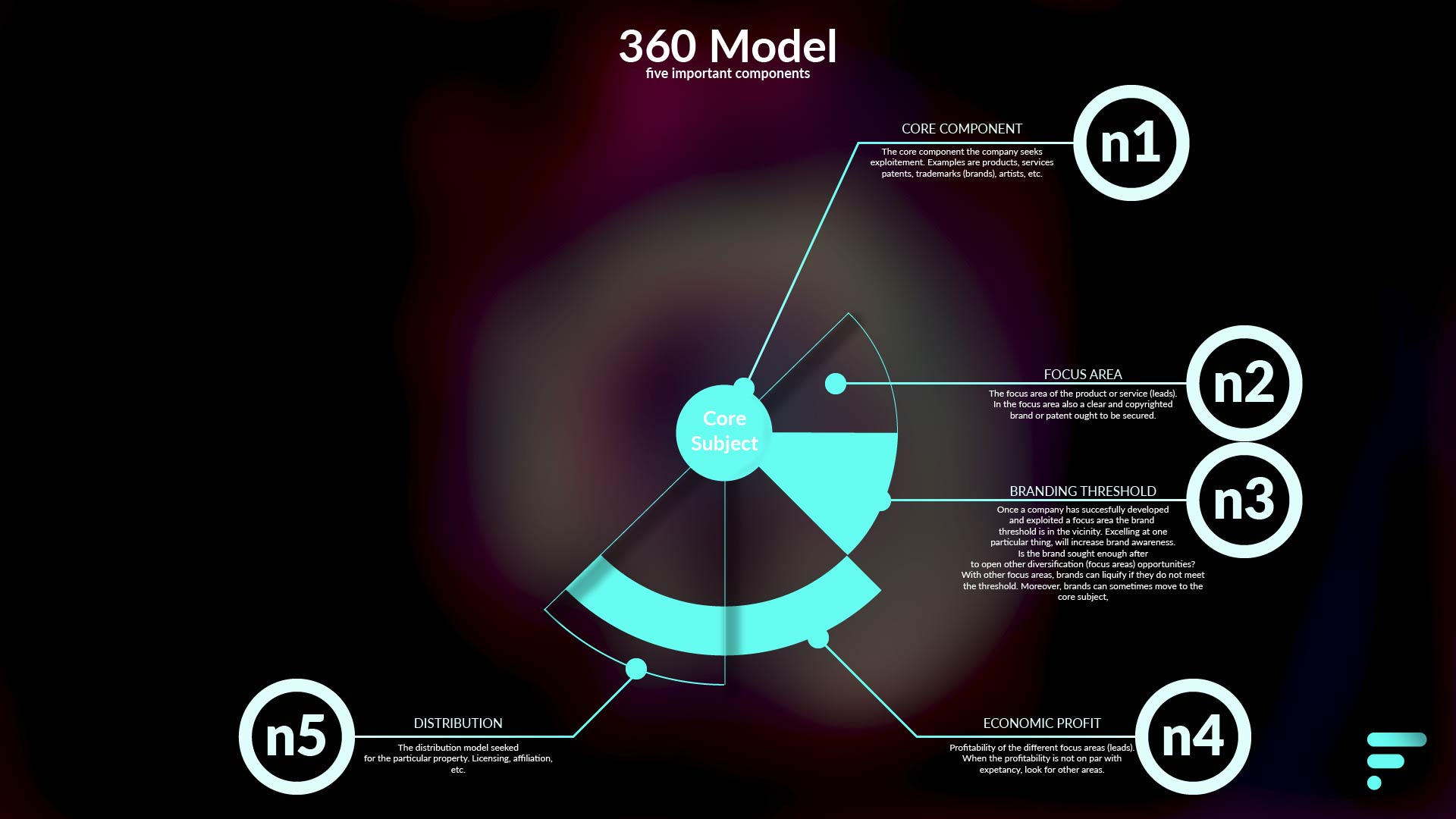

It is true that not everything should be used in a 360 model and not every lead should be pursued. Using the model requires that the central component is sought enough after that it can generate distinct business leads.

Anything else should first focus on its core competencies before pivoting into other roles. Focusing on communication and branding can prep the component to be eventually used on a 360 model. As brands are generally better suited for this model.

Velcro may seem as a patent that only targets the apparel industry, it can also be used for outdoor living equipment like tents. Marketing Velcro in the food and beverage industry, though, may not yield healthy returns. Imagine a teabag using Velcro instead of a string fastening the tea bag. Though possible, it is not the most obvious choice.

Once the central component or core subject is established an assessment needs to be made on the state of the subject. Its focus area (market) and how well sought it is (branding) are particularly important.

In business to consumer (B2C), social metrics can be a good indication to figure out how mainstream the brand is perceived. Views, likes, hearts, or anything else that quantifies the popularity of the component. A fair warning though, social metrics do not constitute a solid business case.

In business to business (B2B), the usefulness for business should be assessed. What benefit does this particular component bring? Is the core market dominated? Does it give an edge, does it increase profit, or does it cut costs? When that is figured the component can be placed at the center.

Alternatively, if you are at the start of a business, you can check this article for information about what makes a company go from zero to one.

From thereon, a business should focus on leads, legal interpretation of the component or leads, the economic viability of leads and the distribution.

With leads it can be anything that pushes towards the goal of the company or the investors.

The legal denomination or interpretation has to do with security. Something that does not have a patent or copyright can be replicable without any legal consequences. Remember that when entering a new market, the company may not own the copyright of say a word or brand.

Economic viability refers to if that endeavor will generate enough returns on its own to justify the approach.

Distribution is closely linked to legal; how will one distribute the component, the company itself, joint ventures, licensing, etc.

Lastly, the company should assess the effect certain options will have on the usage of that component. In other words, what are the risks of (brand) damage by going through with that approach?

McDonalds spinning their brand into hunting or fishing equipment, may generate enough buzz and sales at the beginning, but how will it affect the brand in the long term?

Liquifying the brand more than necessary can have disastrous results on the long-term. But some brands can get away with it. Classic example is the Trump brand, which has been placed on multiple products, objects and even organizations. Whether that has been good or bad for business is debatable.

The other way is true as well, in some cases a move to diversify may result in that brand is boosted in the minds of consumers. Think of corporations affiliating with a charity. Or more specific, Uber offering other types of transportation than what we are accustomed to, like electric skateboards or Segway’s.

Share this Page

Authors note

Although a 360 model is not widely recognized by the name we have explored in this article –matter of fact it can lead to a myriad of different models with the same denomination–, it does leverage on the multi-right-deal as a core component.

For more information pertaining to the diversification or market development look for Ansoff Matrix and the theory behind it.