First Principle in Business

Improve your business with First Principle.

To think in first principle is to think about a proposition that cannot be deduced from other propositions and assumptions.

It is looking at a proposition (or problem) and looking at it from the most basic premises to get fundamental truths. Once “truths” are apparent, you can reason-up and figure out the validity of a proposition or assumption.

Imagine a house that is built with bricks. Bricks are made of sand and alumina. Sand is made of quartz and mica. Quartz is made of silicon and oxygen atoms. Without getting further into chemistry, one can deduct that, arguably, the most fundamental (and attainable) material of a house is sand.

First principle thinking is more commonly used in other fields than business. This type of thinking can be traced back to ancient Greek philosophers (Aristotle, Plato, etc.) and is nowadays used in different scientific disciplines to get to the “true” matter of things.

In business, reasoning from first principle is probably best known through Elon Musk, founder of Tesla and SpaceX. Elon Musk has a physics background and has gone on record to explain how approaching problems from a first principle mindset, has helped him in coming up with solutions that would otherwise “not be possible”.

One example is that Elon Musk tried to buy rockets so he could launch them into orbit for SpaceX. However, the costs of buying a rocket outright (including old rockets from Russia) were too high to make SpaceX a successful company. Confronted with that problem, Musk approached it from first principle thinking. He boiled a rocket down to its most fundamental components and materials. He realized that the prices for materials to build a rocket where much lower than buying a rocket outright. In other words, building a rocket-ship would make more sense for the business model he was creating.

Even though Elon Musk is probably the person most associated with first principle thinking and business, there are other great business leaders whom have approached problems from a similar perspective, like Henry Ford, Charlie Munger, Steve Jobs and many more.

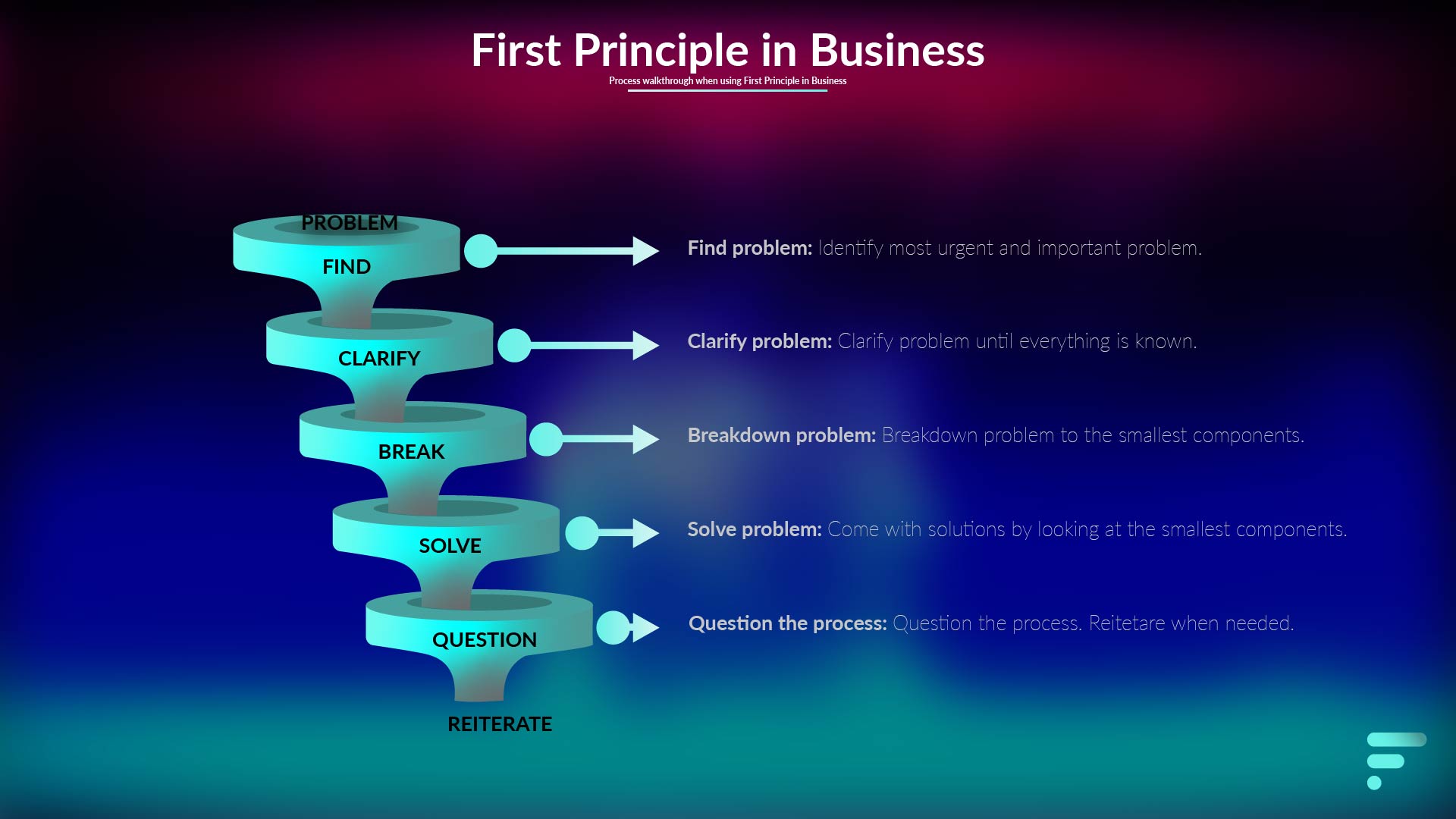

First Principle Model

First principle thinking can be viewed as a counter to biases and tendencies people create from other thinking models, like we do by analogy.

For example, most people have never been ran over by a car. However, we all know that jumping in front of a car will harm us.

We do not need to experience being ran over by a car to understand that. That being said, these are biases and mental models we have created not from experience, but from reasoning.

In business, by reverse engineering certain propositions or problems, you may be able to discover solutions that nobody else has. You will come to knowledge that stands on its own. Reasoning from there allows you to, hopefully, come-up with opportunities no one else sees.

If you would like to know more about creating opportunities no-one else sees, make sure to have a look into the seven questions article.

There are other models that use a similar thinking pattern. For example, disruptive innovation or lean thinking.

Disruptive innovation’s focal point is innovating something to the point that it makes alternatives nearly obsolete. For example, what electric coffee machines did to percolators.

Lean thinking focuses on increasing output and eliminating waste to make an organization more efficient. In order to make an organization more efficient, processes and knowledge needs to be questioned and inefficient routines eliminated.

Whereas disruptive innovation uses first principle thinking to come-up with breakthrough products and services, lean thinking uses first principle thinking to make an organization more efficient.

The difference between the two is important for business development. One focuses on the end-product, what customers want (buy). The other focuses on organization efficiency, making a company more malleable and, by extension, serving stakeholders better.

Both important for business development but very different outcome.

First Principle and Business Development

How to use first principle in a meeting or on your own

The first thing you need to realize when trying to improve something from a first principle perspective, is that change is hard. Compare it to getting out of bed at 3.00 AM. It is not impossible to do it once or twice, but hard when it is more frequent.

Companies experience a similar issue with change. The mantra when things are going well can be summarized in “if it ain’t broke, don’t fix it”. Companies that experience that, get quickly rusted into habits, making change an unpopular priority. Even when change seems, in both foresight and hindsight, necessary.

Proof of that is the many retail shops that have closed in your neighborhood because they failed to embrace e-commerce on time.

The second thing you need to understand is that first principle follows a similar process as critical thinking or scientific reasoning. It follows the process of questioning, reflecting and coming with fundamental assumptions.

For the next part, the Socratic questioning has been adapted to create a model you can use. It should guide you to apply first principle thinking in business scenarios you deem necessary.

It compromises of five parts:

- Finding problem;

- Clarifying problem;

- Breaking down problem;

- Solving problem;

- Question the questions.

I have adapted the model to serve me when approaching things from first principle thinking. The model considers the business environment I find myself in. Feel free to change it to your needs or your experience.

Tools that can help you organize your thoughts, if you are doing it on your own, is a blank canvas and a pen. If you need guiding help, outside of this article, look for Socratic Questions. Just keep in mind that it does not necessarily help with business dilemmas, you will need to adapt that accordingly.

If for any reason the questions do not help. The simple rule of thumb is to ask why to every problem until you get to fundamental truths and, hopefully, have enough information to create solutions to fundamental problems.

Using First Principle in a Meeting

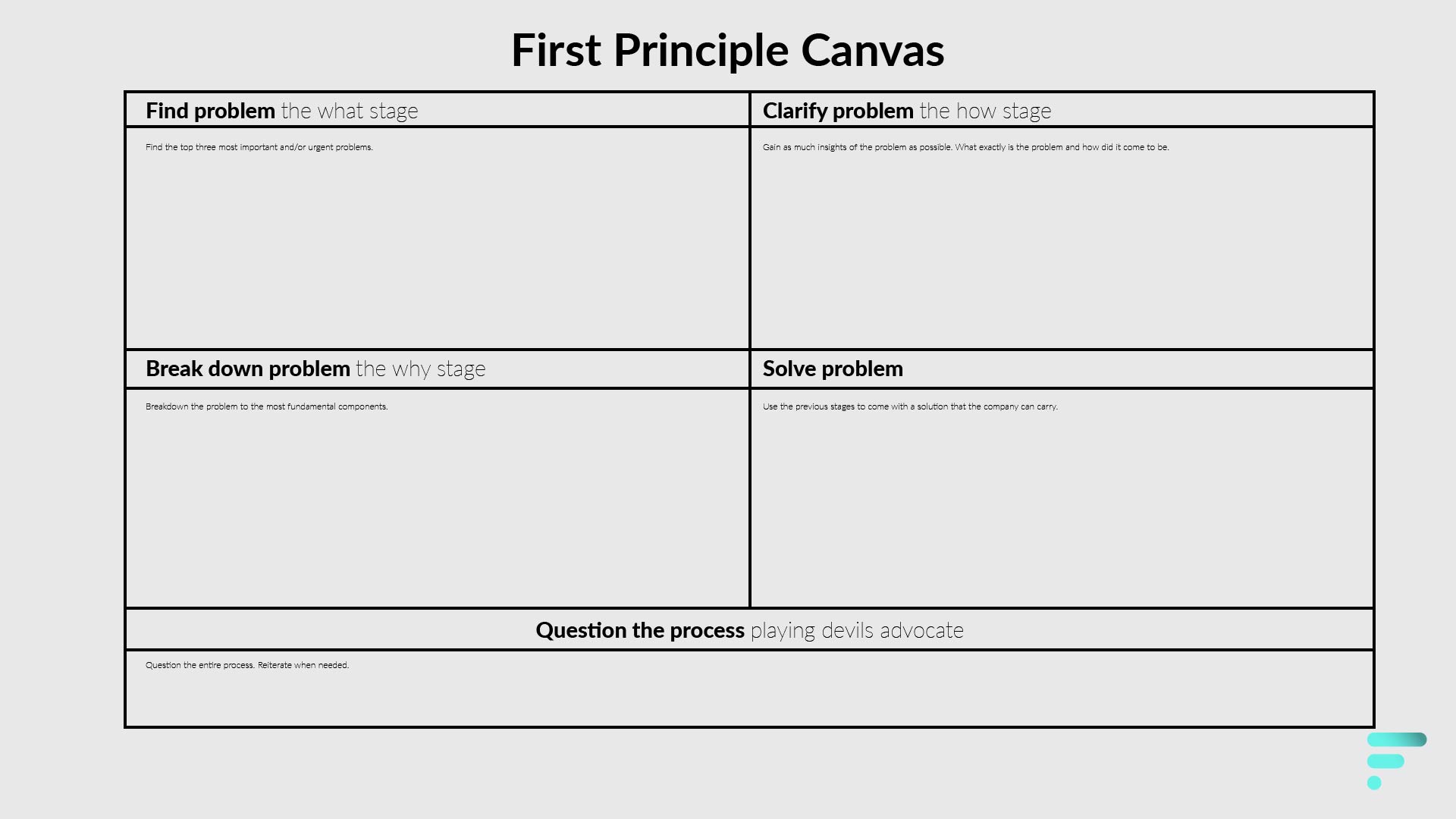

Throughout this article I have written a little guideline on how to approach first principle in a meeting.

If you would like more in-depth information about how to run through a meeting of this type, make sure to get a copy of Design Sprint. You will kill two birds with one stone. How to run a meeting of this type and how to run a design sprint.

Using first principle thinking in a meeting requires a bit more preparation.

I would highly recommend printing and distributing the bellow canvas. This will help guide the meeting more efficiently, as it functions like an agenda of sorts.

Get a whiteboard, divide the whiteboard with a marker into four different quadrants. In each quadrant write the first four pillars as the heading. The fifth is an open discussion. There is no need to write that one.

Actually, if you do, you will realize it will be very detrimental to the productivity in the meeting as its purpose is to question the process and ideas you and your team went through.

Also get different colour whiteboard markers and a whiteboard eraser.

Get everyone a pen and explain what the exercise is about.

Remind everyone that there are no good nor bad answers and that they can write on the paper you gave them.

As for the number of participants needed, less is better.

Lastly, participants will want to solve problems as soon as possible. Ask them to write their solutions on paper and share them during the corresponding stage.

Find Problem

The what stage

As with anything related to business, you need to first identify a problem.

Problems can be something encountered organically in a company, but it can also not be as clear or pressing.

For example, figuring out how to become less dependable of a client or secure continuity are problems that can be deep and require reflection. However, both may not be urgent nor important depending on the risk threshold a company adopts.

Questions that you can ask during this phase, should be about identifying the problem.

Though, it may seem that finding the problem is enough, you should also investigate the feasibility of the solution. This will save time when it comes to the reiterative process, which can quickly become cumbersome when an irresolvable problem arises at a later stage.

You can refer this stage also as the what stage. You do not necessarily have to adhere only to what questions, but it functions as a rule of thumb.

Some example questions you can ask and reflect on are the following:

- What problems are urgent?

- What problems are important?

- What problems are both urgent and important?

- What other problems are both urgent and important?

- How can you verify or disprove whether it is a problem?

- What problems affect the company now?

- What problems will affect the company in the future?

- What are our competitors doing that may cause a problem in the future?

- What problems affect customers?

- What problems will affect our clients in the future?

- What problems affect staff?

- What problems will affect staff in the future?

- What problems affect other stakeholders?

- What other problems are similar in nature?

- How do we know that the problem is a problem?

- Why do we think solving the problem is worth the capital?

- Is the problem solvable?

- How is the problem solvable?

Meeting: Find problem

If you happen to be the one organizing the meeting, your role is to be a moderator or assign a moderator. Throughout the document I will assume that the reader will be the moderator.

The moderator should avoid actively participating in the meeting. They need to watch over that the process people are going through, is in line of first principle thinking.

Moreover, having a moderator helps the meeting to be structured and move forward, before things get out of hand.

If you anticipate that the “find problem” phase is going to be difficult, you can give the participants homework to come with the top three problems that they feel will help the company achieve goals or solve customers’ problems.

If you ask them to send the problems to you, you can use your role as a moderator to identify, before the meeting starts, what the most pressing issues are. This will greatly help moving the meeting forward.

Do be aware that if you do that, you may blind yourself and participants from real problems that nobody has really identified yet.

Use the questions above to guide the meeting. Write the most important problems in the corresponding quadrant on the whiteboard.

Moderate discussions by asking open ended questions. When there are no discussions, the job of the moderator is to instigate discussions and figure out if the problem is really a problem.

When discussions are over. Make sure to narrow down the problems to a maximum of three problems. Rank these problems with the help of the participants.

If the participants are having problems deciding, I suggest using Eisenhower’s matrix to get to the most important and urgent tasks. Do keep in mind that the Eisenhower matrix is not great when you are using first principle with projects that are supposed to be visionary and breakthrough.

Once you have the top three problems written down on the whiteboard and have ranked them. Start with the most important first.

Though it may be tempting to discuss the different problems, only tackle the first one. Later down the line the participants may be able to figure out how to tackle part of the other problems by solving the most important. If not, remind everyone that we can always go back to the drawing board and focus on the other problems.

Clarify Problem

The how stage

Now that you have identified at least one problem, it is time to clarify the problem.

Clarification will help in breaking down the problem to the most essential components. Moreover, it helps in structuring and framing the solutions at the end.

When you clarify a problem, you will want to know exactly what the problem is and how it came to be.

It is during this part that you also challenge the problem. If the problem happens to not be a problem, you need to go back to step one or grab the second problem you came across and forego the clarification process once more.

Similar as before, you could define this stage as the how stage.

Example questions could be:

- Why is it a problem?

- What do we know about the problem?

- What do we not know about the problem?

- What are the blind spots to the problem?

- How do we know about the blind spots?

- Why is solving the problem important?

- How can we look differently at the problem?

- How do the different divisions view the problem?

- How do customers view the problem?

- How does different stakeholders view the problem?

- What other explanations are there for the problem?

- What effect does the problem have on the business?

- Why does the problem affect the business?

- Why does the problem affect customers?

- What is true about the problem?

- How do we know that the problem is true?

- What is causing the problem?

- What are the counter arguments for the problem?

Meeting: Clarify problem

During this stage, as a moderator, you need to make sure that it is clear for everybody what the problem exactly is.

The participants should understand the divisions perspectives on the problem and have a preconception of how it affects them and/or customers.

Whenever you went through the process of clarifying the problem, make sure to summarize that on the whiteboard, taking into consideration every departments vision of the problem.

Ask everybody if they are happy with the summary and if it describes the problem clearly.

If it is not clear, reiterate until everybody is happy. This is important, as later when attempting to solve the problem, it needs to satisfy the interest of everyone (to a degree).

There is a chance that during this stage, you figure out that there are interdepartmental problems. You should check with the managers of the company, a priori, whether that is something you should pursue or not.

If this is not the case for you, or it is irrelevant for the company, go ahead skip to the next section.

If you have figured out that there are interdepartmental problems, you should focus on whether that is the problem you should pursue the rest of the meeting. Open questions (particularly the why question) can help figuring out if that is the real problem or not.

Identifying whether it is just a random squabble or people not liking each other, is much different than a company being sabotaged because departments are competing between them instead of cooperating to serve stakeholders as best they can.

Whether you should pursue it as a primordial problem instead of what everyone agreed to previously, is a question you can ask the group and see if there is common ground on solving that problem.

Personally, I view this as out of scope, as sometimes these problems can be deeply rooted and require many sessions to be solved. Nonetheless, it is very important aspect when the company’s overall goal is to become leaner.

Just remember as a moderator your job is to moderate to the end. The participants will eventually come to a solution. The team will eventually understand that there is a need for change. The problem therein is how long it takes and what the intrinsic motivation is for change.

Break Down Problem

The why stage

Breaking the problem down allows you to look at the fundamental elements of the problem.

Elements that if taken apart will give you a better idea of how to work things out.

Think of it like a Lego construction. Taking pieces apart one by one, will yield building blocks (fundamental elements) that allows you to build something new.

However, before doing so, you will need to make sure to create a blueprint of the current construction (continuing with the Lego example). Take the construction apart. Look at all the elements. Once you have done that you can go to the next stage to see whether you can improve the blueprint, create a complete new-one, demolish it and so on.

During this stage a reward assessment is important. The way you could assess that is by asking three different questions. What happens if you do something, if you do not and if you ignore it. Needless to say, if nothing happens with all three scenarios you will need to go back to a different problem and reiterate.

As with the two previous stages, I refer to this one as the why stage. Like before, this is not necessary to frame the question, but a why question digs deeper and breaks down the problem to the point where we cannot explain things further.

Questions that can help you through are below, remember to ask why after each question:

- What is the essential part of the problem?

- What do we believe is the smallest part of the problem?

- How do we know what the smallest part of the problem is?

- What other components are there to the problem?

- Where does the problem originate?

- What is the blue-print of the problem?

- How can we test the problem?

- Which divisions are hindered by the problem?

- What conflict of interest is there with the problem?

- What ways does solving the problem help the business?

- What are the implications?

- What are the consequences?

- What happens if we do not act on the problem?

- What happens if we ignore the problem?

- What happens if we do act on the problem?

Meeting: Break down problem

The goal of this stage is to look at the problem piece by piece. The why question will be the main tool to dig deeper. Participants will enjoy a thorough understanding of the problem, when you question every answer with why.

The moderator should attempt to guide the conversation to the essential blocks in an ordered manner. You can use semantic groups for that.

The preliminary phase for the moderator is figuring out what the different semantic groups are to the problem. Getting some wrong is fine, but the grouping is important as discussing every single detail can become tedious.

Once everybody has agreed on the different semantics, the moderator needs to group the different blocks accordingly. The moderator can use different colored markers to group or divide the different components.

I generally prefer to make different colored bubbles inside the third quadrant. In each of those bubbles you can write the different components that belong to that semantic group.

For example, an ice-cream parlor in Amsterdam has a problem with staff and clients being able to identify ice-cream correctly. Hazelnut, macadamia, peanut, almond and all other nutty ice-cream have the exact same colour. Similarly, all fruit ice-cream enjoys the same problem. In this scenario, the ice-cream parlor would write a list of the different ice-cream it has and group them by colour.

Once the different semantic groups are ready and clear. The moderator needs to question each single semantic group and narrow down the problem to one single semantic.

The narrower the problem the easier it will be to come to solutions. If later, the participants realize that they chose the wrong group, that is fine. Reiterate and chose a different group.

The reason why you want to group them in semantics, is because it is easier to find and discuss the details of that semantic group. With Some problems it is obvious what the issue is and may not need different groupings. Others can be very complex and draining, needing a strategy to moderate.

Remember, the objective here is to look at things from first principle and solve it from there.

Once the problem semantic has been identified, you will want to narrow the semantic group further down, to the most basic components. If you are short of space on the whiteboard, take a photo of the other semantic groups and erase them (you can print them if you need them or write it once more on the board).

Having a list of the most basic components of the problem, makes it immediately clear the options available to solve it.

The moderator should also figure out if solving the problem brings some sort of reward. In other words, if the problem is worth solving. For example, if ignoring or not acting on a problem, makes the problem go away in the future or does not affect the business in any way, you will have enough ingredients to go back in the reiteration process and select a different problem. If you have followed the other parts, you will have, indeed, done this multiple times.

Once the pieces of the puzzle are known, the participants can jump in what they do best. Solve problems.

Solve Problem

Now that you know what the problem is, how it affects the company, why the problem even exists and what part is exactly responsible for it, it is time to solve the problem.

Continuing the analogy of before, with Lego. By taking apart the building blocks, you can use them to build something new. It may sound cryptic, but once you break things apart and look at the individual components, you should have the necessary information to solve the problem.

During this phase it is important to come-up with different solutions and pit them against each other. Moreover, the solutions should be put into contrast with what the company can do and deliver.

Lastly, it should be clear who is responsible for solving the problem and when the results should be seen.

Some questions I find helpful are:

- How can we solve the problem?

- What other solutions are there to the problem?

- Why is one solution better than the other?

- How does solving the problem affect the business?

- How does the solution benefit the business?

- What is the most important part to solve the problem?

- How do we know that the solution solves the problem?

- What do we have to solve the problem?

- What do we need to solve the problem?

- How does solving the problem affect the finances of the company?

- How is the investment worth solving the problem?

- What do we need to invest to solve the problem?

- What other problems does the solution solve?

- What other problems does the solution create?

- How does the solution affect all stakeholders?

- What happens if we cannot solve the problem?

- What can we learn after solving the problem?

- What knowledge and insights can we use to solve other problems?

- What steps are necessary to solve the problem?

- Who will be responsible for leading the solution to the problem?

- Who will monitor and evaluate?

- How do we measure solving the problem?

- Which solution is the team going to pursue?

- When is the solution going to be implemented?

Meeting: Solve problem

During this stage you will want to pursue one solution but come with a few viable solutions.

The goal of the moderator is to help the participants find the most adequate solutions within the parameters of the company. Some solutions may not be feasible due to monetary constrains. Others may just deviate too much from the company goal.

When the parameters are entirely understood by all the participants. Give them some time to work on solutions. Ask them to write a maximum of five solutions.

Later ask them to present the two top solutions they came up with. As a moderator write the heading of each solution.

Once everyone had a chance to present two solutions (more or less solutions, does not really matter), it is time to discuss the options.

When solutions are competing with one another, remember that that is great, as the participants can potentially pursue other solutions. When the first does not pan out, there is always a second or third that can be tried (though, you will want to avoid that).

Once one or several solutions are within the company’s framework, and they all look as viable solutions. You can ask the people to vote on the solution.

Finally, when the preferred solution has been found. The jobs need to be distributed.

Question the questions

playing devil’s advocate

The last part is reviewing the total process you have gone through. You can question any of the previous phases and see if you have covered things that has not occurred before.

During this stage, it is important to question the process, problem, clarification, break down and solution.

If improvements need to be made, reiterate. If everything seems water proof, you can conclude and execute.

The problem with first principle thinking and business

Despite how rational it sounds to think from first principle, it is not always the best way to go about problems.

Companies are generally entities that are already efficient. Some companies or departments will undoubtedly be more efficient than others, but there are always tradeoffs when approaching things from first principle.

To go back to the example at the introduction, Elon Musk trying to buy a rocket, he first looked if he could buy a rocket. To later figure out he could not afford it, with how he envisioned the space program of SpaceX.

By using first principle, he concluded that building rockets was the way to go. The tradeoff though, is that he lost time by building rockets and enormous amount of capital. Developing rockets takes years and careful financial planning.

Moreover, using first principle does not always yield positive or efficient results. Questioning everything (why) can sometimes result in unsatisfactory answers, wherein a company can conclude there is not much they can do about a problem.

Furthermore, if that type of thinking is incorporated in a company without consequences, it can lead to a company that experiences the dreadful analysis paralysis.

Lastly, approaching sci-fi-esque problems with first principle in business, does generally not lead to any results. Think of teletransportation or creating organic matters. Though the later is, nowadays, probably up for debate.

Share this Page